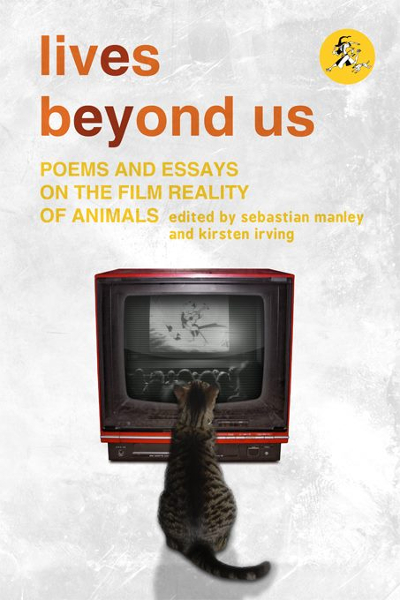

An exciting new volume has been released: Lives Beyond Us – Poems and Essays on the Film Realtiy of Animals. Amongst its many joys, it explores reactions to a death of a deer in Lynch’s The Straight Story, trails dogs in Mon Oncle, interrogates Discovery Channels ‘Battlefied’ wildlife films and interviews a bestiary of animal actors from 70s holiday. There’s also bears (lots of bears). Oh, and an essay from me. It explores the agency of animal subjects in the development of nineteenth century chronophotography, focussing on the physiological practice of Etienne-Jules Marey. It tries to trace out how this apparatus evolved out of the resistances of animals to attempts to understand and record their bodily movements. The animals here include humans, but are not the main focus.

There was a launch, which featured a mix of talks and poetry readings (highlights include the collaborative reading of Angela Cleland’s ‘Alien Vs Jonesy’ and the appropriately solitary reading of Abigail Parry’s ‘The Wolf-man’) as well as a quiz. Though it was a bit difficult for me I did enjoy the spirit of the event – I think such events can sometimes become a little rarefied and it’s great to have a bit of fun in them.

It has been a while since I wrote the essay, and preparing for my reading gave me chance to reflect a little more on the text. I actually re-read a lot of material, as my research in this area stalled due to my lack of language skills. That is, properly understanding the role of animals in Marey’s practice would need detailed examination of primary sources that are in French. The only ones in English were Marey’s books Animal Mechanism and Movement. As such, my work relied heavily on the excellent scholarship already carried out on Marey (especially Marta Braun’s amazing work, a debt I feel I should have acknowledged more clearly in the essay itself) which although impressively thorough, had an understandably different focus. Retrieving the entanglements of animals and equipments from over a century ago needs patient attention to the smallest anecdote, remark and incident. That way one might learn what unexpected directions the research may have taken due to the resistances and accommodations of the animals, instrumentation and other factors.

So where else could this research be taken? My proposition at the end of the essay was to think of practices that do not structure the animal body according to metrical time, but instead allow its own rhythms to create this structure and understanding. In some senses, my investigations into heterodyning address this, though not directly. I might do well to reflect more carefully on what this proposition might entail. There’s a real ethical issue here as well about performing artistic experiments that may distress the animals involved. That said, I can start with myself as an animal, explore my bodily rhythms and see what I can mix them with.

A second route is to develop a similar essay in another area. I’m planning to look a little more closely at the work of Spallanzani, who first hypothesised in the 18th century that bats were able to echolocate. Again I am limited by language – Spallanzani was Italian, so a lot of relevent detail will be lost to me. But it may be worth pursuing even as a short-form essay to inform other work. There’s also other key figures in this history, such as Donald Griffin who finally proved that bats naviagate through sound and not sight. It might be a chance to apply some ideas of Gilbert Simondon, a philosopher with key insights into the development of technology.